By Anya Groner

“If you don’t help him, he’ll die,” Mrs. Stafford said, tapping my cluttered intake desk. We were sitting in an office at Hudson Outreach, a small non-profit in upstate New York. It was June of 2005, and I was the caseworker on duty.

Chris, eighteen, wore an Iron Maiden T-shirt and sat on a vinyl chair in the waiting room, thumbing thru an old copy of Game Informer magazine. I’d offered him a seat in my office but he’d declined, preferring to read while his parents filled me in on his medical history.

“Chris had a heart transplant when he was a kid,” Mrs. Stafford continued. “If he goes even a few days without pills, his white cells go into attack mode. He’ll reject his transplant.”

I copied their social security numbers onto my intake sheet. “How’d you pay for meds in the past?”

Between intakes and phone calls, I hoped to write a report about the discrimination we witnessed daily. I felt certain that if the public knew how terribly welfare treated its beneficiaries, the system as constructed would collapse.

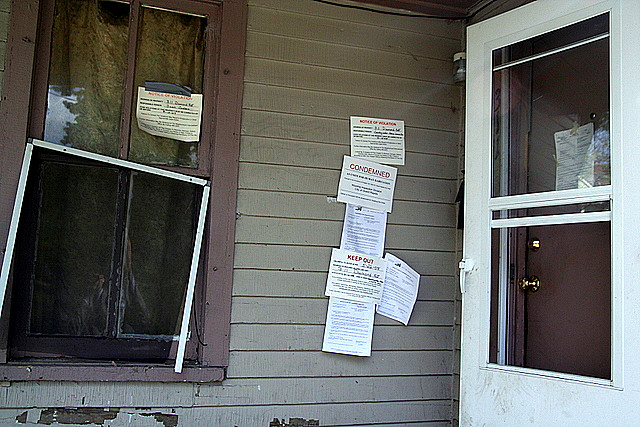

Mrs. Stafford (whose name I’ve changed, along with all the names in this essay) told me they’d been sleeping in their van. “After the eviction, we didn’t have a mailbox. We didn’t get the renewal papers, so our coverage lapsed. Medicaid says it’ll take forty-five days to put us back on. He took his last pill this morning. He won’t make it.”

“You waited until today to ask for help?”

Mrs. Stafford leaned forward. “It’s been a hard year.”

I was twenty-three when I met the Staffords. I’d spent the last two semesters of college volunteering at Hudson Outreach and gotten hooked. In the mornings we passed out free food, and in the afternoon we fought—arguing with government employees about food stamps, Medicaid, emergency rental assistance. After graduating, my boss, Ryan Grant, agreed to pay me six dollars an hour to stay on. Between intakes and phone calls, I hoped to write a report about the discrimination we witnessed daily. I felt certain that if the public knew how terribly welfare treated its beneficiaries, the system as constructed would collapse.

That August I moved from a high ceiling dorm room in a historic landmark to the attic of an old flag shop downtown. The distance was a few miles, but the difference was like flipping channels from Masterpiece Theater to Cops. My dorm had overlooked manicured lawns and a circular garden with an endowment all its own; my new house was two doors down from a grass rotary where women sold blow jobs for $5.

Hudson Outreach helped people in financial crises: men, women, and children who couldn’t afford medicine, or were facing eviction, or were homeless already. On any given day we might hand out food and diapers to thirty families, process four eviction cases, pay for ten people’s medication. We organized turkey drives at Thanksgiving and holiday meals at Christmas. We served free lunches to anyone who showed up in the old gymnasium. We kept a closet full of children’s clothing, ran a hot meals program for the HIV positive, and introduced people who needed furniture to people who had some to give away. And to the extent we were able, we paid people’s rents, utility bills, and prescription costs.

We received about a hundred rent requests a year. Most of those were from people who’d been turned down by Social Services, often for bogus reasons: extra zeroes accidentally added to monthly incomes, errors regarding the number of children in a family’s household. When we found these mistakes—and we often did—we’d call the welfare office and argue like big shot lawyers in movies.

Social Services sucked willpower from the financially vulnerable and, over time, I started to believe the caseworkers employed there enjoyed denying aid to qualified applicants. I dreamed of the day when I’d bring them down.

“So you won’t help this woman flee her abusive husband?” I said once to Strayer, a particularly stubborn case manager with a grating, nasal voice. “What do you mean it’s not financially feasible for her to move?…Who cares if her husband is the breadwinner? He hits her…You want her to stay with him for the money? Listen to yourself…You want proof that he hits her?…Should she go home and get punched and then show you the bruise?…Don’t tell me to act professional. You act professional.”

Social Services sucked willpower from the financially vulnerable and, over time, I started to believe the caseworkers employed there enjoyed denying aid to qualified applicants. I dreamed of the day when I’d bring them down. Information, I believed, would be my weapon. I asked my own clients, refugees from the county bureaucracy, to fill out surveys detailing their mistreatment. I built my arsenal.

From those surveys I learned that people seeking assistance made an average of seven trips to the Social Service offices, after which they were frequently denied help. In the process of seeking aid they lost work hours and had to pay for childcare. On average, they lost about $58 per application, money that could’ve gone towards rent or bills or food. The surveys confirmed something else I already knew. Not only did Social Services illegally deny assistance, they also treated people terribly.

“Working with Social Services is hard and the stress is tremendous,” one man wrote. “You hate it. They make you feel like you’re nobody. Cow dung on someone’s shoes.”

“Social Services is very disrespectful,” complained another. “They put you in a low category, which is not fair.”

When clients lost their patience and became loud or violent they were escorted to the sheriff’s office, conveniently located in the same building. As a client pointed out to me one day, the proximity felt like entrapment.

The year I worked at Hudson Outreach, we found mistakes in over half the Social Service denials we saw. Of the cases we argued, we overturned a third. People who had previously been denied heating assistance or rent got much needed checks from the state. Another third of our clients received grants from us. The final third received nothing, not from us and not from Social Services. Often they became homeless.

“You mean to tell me,” I said to Mrs. Stafford, “that the caseworkers at Medicaid are making your son wait for the medicine he needs to survive?”

“When Chris was fourteen, he stopped taking his meds without telling us. He was in intensive care for weeks.” She put her hand on her husband’s knee. “He nearly lost his heart.”

“You have evidence that your son will die if he goes without medicine?”

“I have medical records,” she said.

I stood up. “Will you excuse me while I talk this over with my boss?” I couldn’t wait to tell Ryan about this latest injustice.

“Write a letter to the paper,” the receptionist said when she overheard the story.

“Call his caseworker first,” Ryan countered. “Social Services is killing this kid.”

“Would you like red beans or black beans?” we asked our food pantry recipients. Never did we say, “Name your favorite fresh fruit and the cut of meat you’d like to roast tonight.” When accepting charity, choice rarely factors in. At Hudson Outreach, poor people had their food chosen for them. And in order to get their beans, rice, canned tomatoes, and evaporated milk, they had to answer a series of personal questions and show official documentation.

One Thanksgiving, a board member called from the parking lot, requesting help carrying a frozen turkey from her trunk to our office…I lugged the bird up three flights of stairs. Somewhere near the top, I noticed the expiration date. It was seventeen years old.

But, like our clients, Hudson Outreach was at the whim of donors. When the 2004 tsunami hit the coasts of Thailand, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and India, many of our regular donors gave to international charities instead. We had to curtail winter programs—less meat in our freezer, fewer coats to give away.

When our donors met the actual people they were helping they often didn’t like them. During our Secret Santa drive, volunteers sometimes refused to drop gifts at houses with TVs inside. They got angry when clients had cell phones or in some other way didn’t match their expectations. Other times, the donations we got were too disgusting to pass along—soup cans that bulged with botulism and diapers so dry rotted they crumbled in our hands. One Thanksgiving, a board member called from the parking lot, requesting help carrying a frozen turkey from her trunk to our office. “Can you find a deserving family?” she asked. I lugged the bird up three flights of stairs. Somewhere near the top, I noticed the expiration date. It was seventeen years old.

After discussing Chris’s medical condition with Ryan, I called the Staffords back to my office. This time Chris came too.

“We’re not going to be able to pay for your pills,” I told them. “What we can do is get in touch with Chris’s Medicaid worker and try to force the state to pay.”

“You’re not going to help?” Mrs. Stafford said. She turned to her son. Chris had taken a yo-yo out of his pocket and was winding the string tightly around his wrist.

“Our goal is to help you and a lot of other people at the same time. This forty-five day waiting period hits everyone hard. Your case is an opportunity for us to call Medicaid out.”

Mrs. Stafford nodded. “How long will it take?”

“I don’t know,” I said.

No one said anything, but we all were thinking it: we were using Chris’s life to make a point.

Chris and his parents came to the outreach center at the end of the month, which is the time, for those who rely on government checks, when food stamps have run out, disability has been spent, and rent is due. My patience was short and everyone was in crisis. A heroin addict needed methadone. An insulin-deprived diabetic was going blind. When clients started to hyperventilate, I handed out cups of water to slow down their breathing and stop their tears.

I squeezed in calls to Social Services between casework. Though I dialed them frequently, I dreaded these conversations. The receptionists recognized my voice. “What’s your complaint this time?” they’d say. “You’ll have to speak up. Who is it you want? Strayer? She’s out to lunch. You want me to take a message? You already left a message. It’s not my fault if she’s been at lunch all day. What do you want me to do about it?”

Often it would take four or five calls to get past the receptionists. When I finally reached Chris’s caseworker, hours after the Staffords had arrived, I found out more of his story. He had a long mental health history, including the suicidal period that caused him to forgo his heart medicine when he was fourteen. Two weeks before, his caseworker agreed to speed up his Medicaid application if Chris saw a counselor. She gave him three days. Saturday. Sunday. And Monday—Memorial Day. The mental health offices were closed the whole time. On Tuesday, when Chris came by her office, she told him it was too late. He’d have to wait forty-five days.

“Do you understand he could die?” I asked.

“Doesn’t your organization pay for prescriptions?” she asked. “Why don’t you buy his pills?”

I collapsed in an enormous yellow armchair in Ryan’s office. The room overflowed with unusable donations. Gray computer monitors lined one wall. Children’s books teetered in piles. On Ryan’s desk, beside a pile of case folders, a three-armed teddy bear lay face down, a clothespin clipped inexplicably to its back. I told Ryan that I was getting nowhere. It didn’t matter if Social Services was wrong. They weren’t going to pay.

Ryan folded his arms and leaned back. “Well, neither are we,” he said.

Objectivity is required when conducting an evaluation, and it’s here where I felt most challenged. I took everything personally: Strayer’s six-hour lunch breaks, Chris’s adolescent malaise, Ryan’s determination to teach the system a lesson. When writing my report, I tried to write fair surveys and acknowledge the ways Social Services actually succeeded at their mission, but the truth is I dreamed of vengeance. I hoped my work would cause a tidal wave of policy change. The idea frightened and excited me. I would make my TV debut and then a mob would take to the streets, throwing empty pill bottles and bricks at the gray building where Social Services is housed. In my wildest fantasy I imagined running for mayor and replacing the incumbent Democrat, who drove around town in a golden Mazda with a license plate that read Ms. Mayor. I would fire the Social Service employees who talked down to me on the phone. Chris’s caseworker, Strayer, would go first. After her, the receptionists.

The standoff between Ryan and Social Services lasted a week, and the adrenaline I felt when I first met the Staffords faded. Most of my time was spent waiting for phone calls. Chris read magazines in the waiting room and struck up conversations with other clients. Mr. and Mrs. Stafford whispered quietly under the mural where a school group had long ago painted the phrase Sharing is Caring is Sharing in fat pastel letters. Behind their chairs, a googly-eyed Duck held out a daisy. Between phone calls and new intakes, I worked on my report.

The situation was grim. Homelessness in the county tripled between 1999 and 2005. Subsidized housing was getting cut, and rents were on the rise. Because of a glitch in the state budget nearly all the youth programs in New York lost their grants. This included numerous after school and job training programs, as well as the grant that funded my own employment—though Brian managed to scrounge enough money to keep me on. Kids had nowhere to go, and working parents had no childcare. Unemployment was rising. Our caseload tripled and our budget decreased.

A homeless woman got turned away from Social Services because “she was not pending an eviction,” and a single mother who’d been kicked out of her house by her husband received the news that she and her children “had no immediate needs.” For many of our clients, the food pantry had become more like a permanent alternative to the grocery store than a one-time lifesaver. I struggled to transform personal horror into persuasive statistics to include in my report. And when I met with a sociology professor to ask for help, she ruefully told me that the line of people who thought they could change the system with a written report was already a long one.

When I hung up the phone, the Staffords peered at me, anxious for news. Mrs. Stafford raised her hand to her chest, her palm over her heart, her fingers squeezed tight. A local drugstore, Fifth Street Pharmacy, cut us a deal on Chris’s pills while we waited for Medicaid to respond. Of the whole family, Chris seemed the most relaxed, bored by the bureaucracy on which his survival depended. “I just don’t know,” I kept telling his parents. “We have to wait it out.” After getting nowhere with Chris’s caseworker, I called the caseworker’s manager.

“You’ll have to schedule a hearing if you want to overturn our decision,” she said. “That’ll take weeks.”

Tired of climbing the chain of command, I turned the case over to Ryan. “I’ve taken this as far as I know how,” I told him. Three days later, he called me to his office.

“I cut a deal with Bob,” he told me. Bob was the commissioner of Social Services. We caseworkers weren’t allowed to call him but, when times were dire, Ryan would ring him up. The men weren’t exactly friends, but they maintained a mannered civility. “We’ll pay for Chris’ prescription, and Medicaid will reimburse us,” Ryan said. “In a month and a half, Medicaid will pay for his pills directly. We did the best we could.”

I’ve heard it argued that non-profits function as a sort of safety valve, releasing just enough steam so that instead of organizing for systemic change, people compete for assistance.

“Congrats?” I said. It hardly seemed a victory. Chris’s make-do heart ticked tenuously on, but the state bureaucracy remained untouched. The only player who seemed to gain anything at all was our little agency. I wandered to the waiting room to break the news to the Staffords.

“Thanks, hon,” Mrs. Stafford said. “I know you went to bat for us.” The nuances of our standoff didn’t interest them. Chris’s medicine supply was reliable again.

I watched out the window as they walked once more to the pharmacy. After that, where would they go? To celebrate in their van?

Not long after the Stafford case concluded, I finished my report. Ryan and I never discussed what we’d do with it, but I’d assumed he’d aim high, mailing copies to newspapers and politicians. I’d seen other reports distributed this way and to good effect. But, when the time came, Ryan balked. A few weeks after the Stafford case, Bob offered him another deal. Social Services would give Hudson Outreach a $10,000 rolling grant to cover prescriptions for pending Medicaid applicants, and we would stop challenging the forty-five day waiting period. Our agency wouldn’t have to spend time distinguishing “worthy” applicants from “unworthy” ones—and people who needed help would have yet another agency on their list of stops.

“I’ll put your recommendations in our yearly newsletter,” Ryan told me, referring to the grand finale of my thirty-page report. I’d included suggestions like the need for more direct communication, a new intake process, and mandatory lessons in basic respect. In isolation they sounded vindictive and banal, but I was too tired to argue. I bought a plane ticket to visit my sister and gave my two weeks notice.

After I quit, I heard rumors that the newsletter pissed Social Services off, but as far as I know, nothing came of it. Save for a few college interns and some local activists, no one ever read my report. When I reread it now, I can feel my old desperation and hope. I wanted to fix everything at once: poverty, prejudice, bureaucracy, general indecency. In the introduction, I wrote:

I’ve heard it argued that non-profits function as a sort of safety valve, releasing just enough steam so that instead of organizing for systemic change, people compete for assistance. For the professional service workers who encounter and, at times, exacerbate social disparity, something happens internally. During my year at Hudson Outreach I grew mean. My friends were struggling through their first years out of college. Some had difficult break ups, some fell in love. I stopped caring. My emotional range contracted, and I vacillated between bitterness and outrage. I obsessed about families I barely knew and reported the horrifying details of welfare cases to my friends. My hatred for Social Services kept me up at night. I skipped parties and avoided phone calls. In the hours after work when I was too drained to socialize, I’d sit in my attic room, listening to music and sewing small squares of fabric into larger squares. That spring, I finished a quilt.

The end of idealism is sad. It requires lowering expectations and reluctant acceptance of disappointment. I’d hoped to make change with pie graphs and subheadings and thoughtful analysis. I’d believed society had an interest in improving itself.

When I decided to quit, friends told me that the end of idealism is the beginning of awareness, that awareness is power, even when it shuts you down.

On my last day at work, a woman tapped my shoulder. “Excuse me, ma’am,” she said, glancing towards the waiting room, “but that man just pulled a needle out of his pants.”

“Oh yeah?” I said, glancing up from the papers I was filing, “and what do you want me to do about it?”

“I just thought you’d want to know.”

“Thanks,” I said. “Now, I do.”

Anya Groner teaches English at Loyola University in New Orleans. Her stories and essays can be found in Ninth Letter, The Oxford American, Gigantic, Meridian and The Rumpus.